Oregon’s $1,600 rebate has just gained a new set of endorsements ahead of the November election, which will put the measure in front of voters as a final decision. Newsweek spoke with experts about what this means for families—and for the state.

Measure 118 will be on the ballot for Oregonians this election. The law would call for a $1,600 direct payment to all Oregon residents.

The Community Alliance of Tenants and Portland Tenants United, which are tenant-rights organizations fighting for affordable housing, both endorsed the rebate this week.

“Measure 118 is a lifeline for Oregon renters facing skyrocketing costs,” said Kim McCarty, Executive Director of Community Alliance of Tenants in a statement. “This rebate provides immediate relief in a volatile and often predatory housing market. For too many, a $1,600 check is the difference between a stable home and homelessness.”

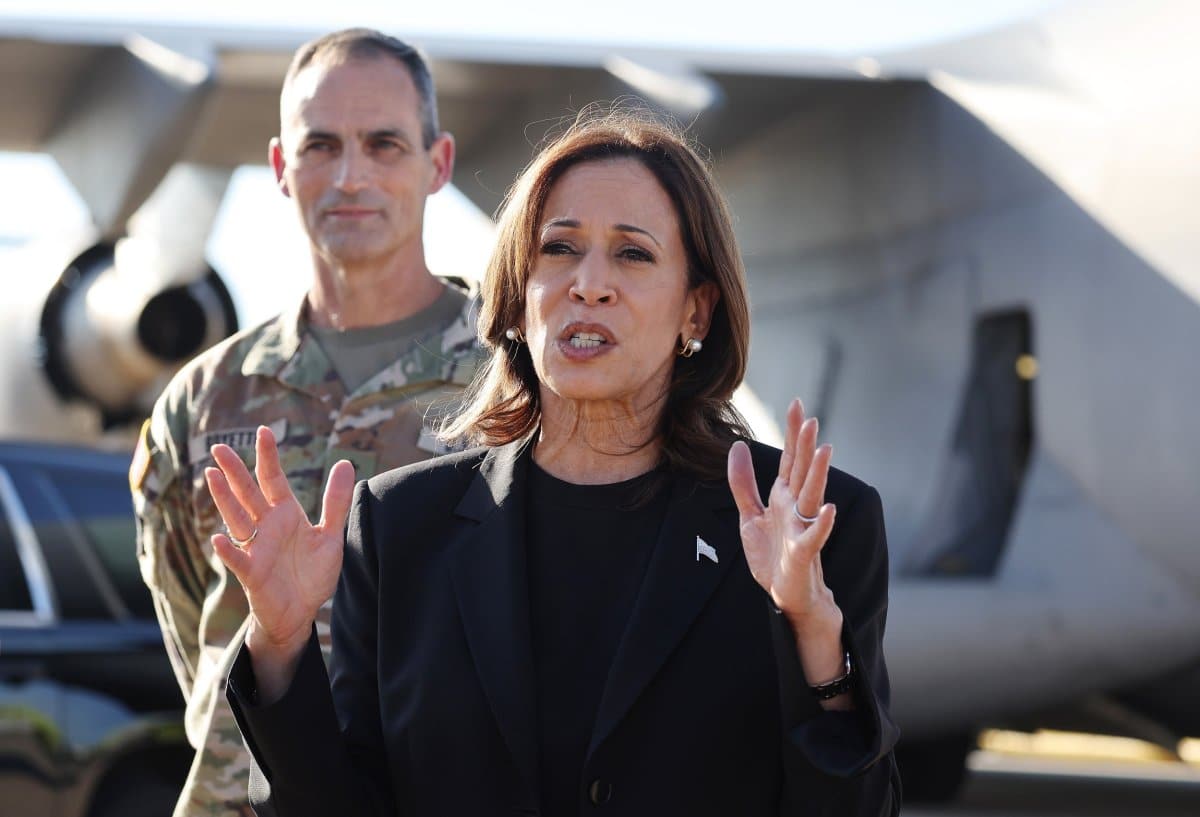

Democratic gubernatorial nominee Tina Kotek speaks with members of the media before casting her ballot at a ballot drop box on November 2, 2022 in Portland, Oregon. Kotek has come out against Measure 118, which would provide all residents $1,600 as a direct payment.

Mathieu Lewis-Rolland/Getty Images

The rebate, which would provide the no-strings-attached payment to all residents, could help curb some of the affordable housing issues the state has faced.

According to a recent report from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, nearly half of all renters in the state paid more than 30 percent of their income on housing, and more than half said they didn’t have enough money after paying rent to afford necessities like food and child care.

“This affordability crisis has been exacerbated by a shortage of affordable housing units and rising rents,” McCarty said. “As a result, there is a growing need for assistance programs and policies, such as Measure 118, that can help Oregonians manage rental prices and avoid housing instability.”

For those living in the Portland metropolitan area, the rebate would cover roughly one month of rent, but costs have been rising for many.

“When rents go up so much, tenants report cutting back on food and medicine to make up for it,” Leeor Schweitzer, organizer with Portland Tenants United, said in a statement. “The Oregon Rebate won’t replace needed tenants’ rights, but it will wipe away this rent increase and provide much needed support for low-income renters.”

If passed, every resident who has lived in Oregon for more than 200 days will get the payment. That includes minors.

To get the $1,600 payments in the hands of Oregonians, however, the state would have to increase its minimum corporate tax rate after $25 million of in-state revenue by 3 percent.

Drew Powers, the founder of Illinois-based Powers Financial Group, said if the state adopts the rebate, it would be a stepping stone to a universal basic income.

Still, the taxes necessary to get the payments passed could block the measure from getting passed.

“New taxes are rarely welcomed, regardless of if they are at the corporate or personal level,” Powers told Newsweek. “Businesses are concerned that the tax targets revenue figures, not profits, which means low-margin industries will be forced to pass on the cost to consumers.”

For individual voters, those higher costs could be a concern that keeps them from approving the measure on election day. At the same time, some individuals will be concerned with how the state would then calculate low-income benefits, such as SNAP and Medicaid.

“Oregon Measure 118 is most certainly imperfect, but it is promoting the wildly popular, and possibly inevitable idea of Universal Basic Income,” Powers said. “It will be interesting to see how it evolves, what eventually gets passed, and what adjustments other states will make.”

Michael Ryan, a finance expert and the founder and CEO of 9i Capital Group, called the rebate “substantial” but warned that big employers like Intel and Nike aren’t thrilled about what the taxes would mean.

“We’re seeing more states experiment with various rebate structures,” Ryan told Newsweek. “But Oregon’s proposal is one of the most aggressive. It’s part of a broader trend of states trying to address income inequality through direct payments.”

Due to Oregon’s progressive tendencies and its reliance on big corporate employers, Ryan said it’s a “toss up” if the proposal actually gets passed in November.

Alex Beene, a financial literacy instructor for the University of Tennessee at Martin, said one of the biggest cons is the possible higher prices that businesses would enact on residents.

“The rebate, though, could end up producing more harm than good,” Beene told Newsweek.

“A 3 percent tax on the state’s corporations could equate to those same businesses passing on those costs to the consumer. A rebate certainly would be nice to have, but if you’re having to pay significantly more for items you’re purchasing from these same businesses, it could in effect eliminate any financial gain a rebate would produce. “

The rebate, if passed, would go into effect for taxes in 2025 and be paid out for the first time in 2026.

While rebates wouldn’t immediately be as high as $1,600 based on tax revenue, a state analysis estimated the rebate would get up to $1,605 by 2027.

Democratic Governor Tina Kotek has come out against the measure in recent months, telling voters it could end up having severe consequences for the state.

“It may look good on paper, but its flawed approach would punch a huge hole in the state budget and put essential services for low-wage and working families at risk,” Kotek said previously, as reported by the Capital Oregon Chronicle.