It sounds disgusting at first: smell the essence of an old corpse.

Researchers who were curious about the smell of well-preserved Egyptian Mummies discovered that they actually smelled pretty good.

Cecilia Bembibre is the director of research for University College London’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage. She said: “In books and films, horrible things happen to people who smell mummified corpses.” “We were surprised by the pleasantness of these people.”

What sounded like a wine-tasting exercise was described as “woody”, “spicy”, and “sweet”. There were floral notes, possibly from the pine and juniper based resins that are used to embalm mummies.

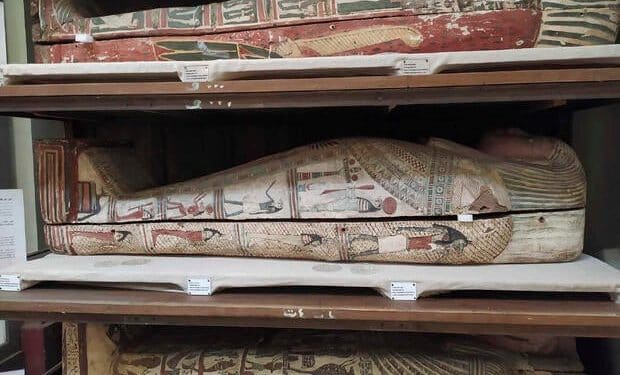

The study, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society on Thursday, used both chemical analysis as well as a panel of sniffers to assess the odors of nine mummies that were either stored or displayed at the Egyptian Museum of Cairo.

Bembibre said that the researchers wanted to study the smell of Mummies in order to understand it better. It has been a topic of interest for both the public and researchers. For good reason, archeologists, historians and conservators have dedicated pages to this subject.

Mummification was a practice that was largely reserved for pharaohs and nobility. They used waxes, oils and balms in order to preserve their bodies and spirits. This practice was reserved mainly for royalty and pharaohs . The pleasant smells of a deity or purity were associated with the good smells.

Researchers from UCL in London and University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, were able, without sampling mummies themselves which would have been invasive, to determine whether the smells came from the archaeological object, pesticides, other products used to preserve the remains, or deterioration caused by mold, bacteria, or microorganisms.

Matija Strlic is a professor of chemistry at the University of Ljubljana. She said, “We were worried we would find notes or hints of decaying corpses, but that wasn’t the situation.” “We were worried about microbial decay, but this was not the situation, so the museum’s environment is quite good when it comes to preservation.”

Strlic said that using technical instruments to measure air molecules emitted by sarcophagi in order to determine their state of preservation without having to touch the mummies , was like finding the Holy Grail.

He said: “It could tell us what social class the mummy belonged to and thus reveals a great deal of information about mummified bodies that are relevant to not only conservators but also curators and archeologists.” “We think that this approach could be of great interest to other types museum collections.”

Barbara Huber is a German postdoctoral research scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology who wasn’t involved in the study. She said that the findings provided crucial information on compounds which could degrade or preserve mummified remains. This information can be used to protect ancient remains for future generations.

Huber added that the research highlights a major challenge: The smells we detect today may not be the same as those of mummification. Over thousands of years evaporation and oxidation have altered the original smell profile.

Huber published a study in which she analyzed residues from a jar containing mummified organs to identify embalming agents, their origins, and what they revealed regarding trade routes. She worked with a fragrancer to create a scent interpretation of embalming, called “Scent of Eternity,” as part of an exhibition at Denmark’s Moesgaard Museum.

Researchers hope to achieve a similar result, by using their findings to create “smellscapes”, which artificially recreates the scents that they detected. This will enhance the experience of future museumgoers.

Bembibre explained that museums are often called “white cubes” because they encourage visitors to read, see and approach objects from a distance. “Observing mummified corpses through a case of glass reduces the experience, because we can’t smell them.” We can’t experience the mummification in a way that helps us understand the world.