2/12/26 — 6:50 AM

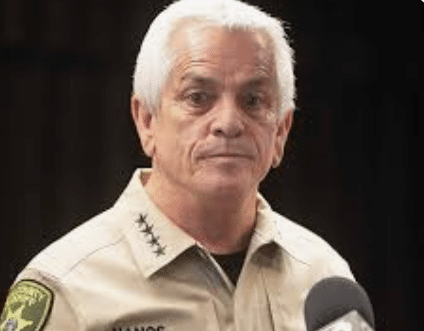

Senior Editor David Ravo takes a hard look at what increasingly appears to be a Pima County Sheriff’s Office in disarray under Sheriff Chris Nanos. From mishandling the original crime scene to failing to grasp the seriousness of the Guthrie kidnapping, Nanos has shown a pattern of hubris that now extends to his latest decision: sending evidence from Nancy Guthrie’s property to a private lab in Florida instead of turning it over to the FBI for processing at Quantico. That kind of misleading judgment hasn’t just complicated the investigation—it has placed the entire case, and Nancy Guthrie herself, in deeper jeopardy.

The public does not expect perfection from law enforcement, but it does expect competence, seriousness, and a basic understanding of the gravity of a kidnapping investigation. What it has received instead is a series of baffling decisions, contradictory statements, and a sheriff who seems more concerned with projecting confidence than demonstrating it. The Guthrie case is not a routine missing‑persons report. It is a rare, high‑risk kidnapping in the United States, made even more complex by a cryptocurrency ransom demand—an element that requires immediate federal coordination, digital‑forensics expertise, and a disciplined investigative strategy. Yet the sheriff’s actions suggest a man who either does not understand the stakes or refuses to acknowledge them.

The first cracks in the investigation appeared almost immediately. The victim’s vehicle, left in the garage, was not towed to the police station for forensic processing. In any kidnapping case, a vehicle is a primary crime scene. It is a container of evidence—fibers, fingerprints, digital devices, GPS data, trace materials, and environmental clues that can help reconstruct the victim’s last movements. Leaving it behind is not a minor oversight; it is a fundamental investigative failure. It delays forensic analysis, risks contamination, and signals a lack of procedural rigor at a moment when the investigation needed to be airtight. When a sheriff’s office mishandles something as basic as securing and processing a vehicle, the public is right to question the competence of the leadership overseeing the case.

Then came the decision to open the victim’s home to the press—only to close it again. Crime scenes are controlled environments. They are not media backdrops. Allowing cameras inside, even briefly, raises questions about chain of custody, evidence preservation, and the seriousness with which the scene was being managed. It also creates confusion, inconsistency, and the appearance of a department improvising its way through a crisis rather than following established protocols. These are not abstract concerns. They are foundational elements of investigative integrity. When the sheriff’s office makes errors that would be unacceptable in a routine burglary case, the public is right to ask how such errors could occur during a kidnapping. But the most troubling decision came later, when evidence recovered from Nancy Guthrie’s property—evidence the FBI expected to send to Quantico—was instead diverted by Sheriff Nanos to a private lab in Florida. This is not a matter of preference. It is a matter of jurisdiction, expertise, and national‑level investigative standards.

Quantico is the gold standard for forensic analysis in federal kidnapping cases. It is where evidence is processed with the highest level of scientific rigor, chain‑of‑custody protection, and interagency coordination. Sending evidence to a private lab, without clear justification, undermines the integrity of the investigation and raises serious questions about motive, judgment, and transparency.

Why would a sheriff bypass the FBI in a case that clearly requires federal involvement? Why would he choose a private lab over the nation’s most advanced forensic facility? Why would he make a unilateral decision that could compromise the admissibility, credibility, or scientific reliability of the evidence? These are not rhetorical questions. They are questions the public deserves answers to. And they are questions that, so far, Sheriff Nanos has not adequately addressed.

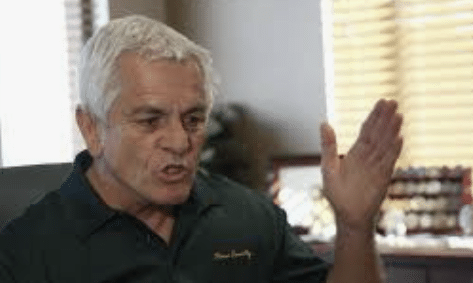

The sheriff’s pattern of misleading statements only deepens the concern. He has repeatedly assured the public that he is “focused” on the investigation, “deeply involved,” and “working around the clock.” Yet his actions tell a different story. When he appeared courtside at a Saturday night basketball game—smiling, relaxed, and visibly off‑duty—the disconnect was impossible to ignore. Optics matter. Leadership matters. And in moments of crisis, the public watches closely not because they are nosy, but because they are scared. A sheriff who claims to be fully engaged in a rare, high‑stakes kidnapping investigation should not be photographed enjoying a night out. Even if he had spent the entire day in meetings, even if he had been briefed by detectives, even if he had spoken with the FBI earlier that afternoon, the moment he stepped into that arena he created a contradiction between his words and his actions.

Public trust is fragile. It is built slowly and lost quickly. And nothing erodes trust faster than the perception that an official is not taking a crisis seriously. This is not about policing his personal time. It is about the message his choices send. When a sheriff attends a basketball game during an active kidnapping investigation, the message is not “I’m working hard.” The message is “I have time for this.” And that message is misleading.

The Guthrie case is not just rare—it is technically complex. Cryptocurrency ransom demands introduce layers of difficulty that traditional kidnapping cases do not. Tracking digital wallets, analyzing blockchain movements, coordinating with federal cyber units, and navigating the legal and jurisdictional complexities of digital extortion require specialized expertise. Local law enforcement cannot handle this alone. They need federal partners. They need the FBI. And the sheriff should be meeting with them. Kidnapping cases involving cryptocurrency are time‑sensitive. The longer the delay in coordinating with federal cyber teams, the harder it becomes to trace transactions, identify wallet owners, or intercept funds. Digital trails cool quickly. Criminals move assets rapidly. Every hour lost is an opportunity lost.

So when the sheriff is photographed courtside, the public is not wrong to wonder why he isn’t in a briefing room, why he isn’t coordinating with federal agents, why he isn’t doing everything possible to bring Nancy Guthrie home. These are not unfair questions. They are the questions any reasonable person would ask. And they are questions that highlight a deeper issue: the sheriff’s apparent inability to grasp the seriousness of the situation.

Sheriffs are not just law‑enforcement officers. They are elected leaders. They are accountable to the public. They are expected to model seriousness, discipline, and transparency—especially during crises. When they make mistakes, those mistakes are not private. They are public failures with public consequences. The early errors in the Guthrie investigation were not small. They were not technicalities. They were fundamental lapses in investigative procedure. And when those lapses are followed by a public appearance that contradicts the sheriff’s stated level of focus, the public is left with a troubling picture: a leader who says one thing and does another.

Behind every kidnapping case is a family living through the worst days of their lives. They are not thinking about optics. They are not thinking about press conferences. They are not thinking about public perception. They are thinking about their loved one. They are thinking about the clock. They are thinking about the terrifying possibility that time is running out. When a sheriff says he is focused, that family takes him at his word. They cling to it. They need it. They need to believe that the person in charge is doing everything possible. So when that same sheriff is photographed courtside, the emotional impact is not abstract. It is personal. It is painful. It is destabilizing.

Leadership is not just about managing an investigation. It is about managing the emotional reality of a community in crisis. And misleading the public—through words, actions, or contradictions—deepens the trauma of those already suffering. The sheriff owes the public an explanation. Not a defensive one. Not a dismissive one. A real one. Why was the vehicle not immediately processed? Why was the home opened to the press? Why was it closed again? Why was evidence diverted to a private lab? Why was he at a basketball game during an active kidnapping investigation? What steps has he taken to coordinate with federal partners? What corrective measures have been implemented to prevent further errors? These are not hostile questions. They are necessary ones. Transparency is not optional in a crisis. It is the foundation of public trust.

The Guthrie investigation is still ongoing. There is still time to correct course. There is still time to demonstrate seriousness, urgency, and leadership. But that requires a shift in approach. It requires the sheriff to prioritize transparency over optics. It requires him to acknowledge errors rather than gloss over them. It requires him to align his actions with his words. It requires him to treat this case with the full weight and focus it demands. The community is watching. The family is waiting. And the sheriff’s credibility is on the line. This is not a moment for courtside appearances. It is a moment for leadership. A kidnapping is one of the most serious crimes a community can face. It demands the full attention of every agency involved. It demands coordination, discipline, and urgency. And it demands that the sheriff—the elected leader entrusted with public safety—demonstrate through his actions that he is fully committed. Anything less is misleading.