12:30 PM — David Ravo, Sr. Editor, provides an editorial on the shifting relevance of the Equal‑Time Rule. Originally designed for a broadcast era where airtime was the currency of political influence, the rule now sits in a media landscape where perception matters more than minutes on television. Today, the real contest isn’t over who gets airtime — it’s over who appears silenced, who gets platformed, and who gets redirected to digital side‑channels. In many cases, the perception of censorship carries more cultural weight than the airtime it supposedly replaces.

The Equal‑Time Rule is misleading because it gives the public the impression that television networks are legally required to provide balanced political airtime in a world where the rule barely applies anymore. It was created for a broadcast era defined by scarcity, when a few networks controlled the national conversation and airtime was the only path to public visibility. Today, political communication happens across dozens of platforms—YouTube, podcasts, streaming services, social media, and digital‑only segments that reach far more people than traditional television. The rule does not apply to any of these spaces, yet audiences still believe it governs them. This gap between what the rule actually covers and what people assume it covers creates confusion, misplaced outrage, and the false belief that networks are violating a fairness standard that no longer reflects how media works.

The rule is also misleading because it suggests that equal minutes on television translate to equal influence, when in reality influence has shifted to digital platforms that operate outside the rule entirely. A candidate who appears for five minutes on a late‑night show may reach fewer people than a candidate who posts a 30‑second clip on TikTok. A conversation uploaded to YouTube can outperform a primetime interview. A podcast appearance can shape public opinion more than a televised debate. The Equal‑Time Rule does not account for any of this, yet it continues to be treated as if it ensures fairness across the entire media ecosystem. It doesn’t. It can’t. It was never designed to.

The rule is further misleading because it forces entertainment shows and talk shows to make distribution decisions that look political even when they are simply procedural. When a late‑night show moves a political interview from broadcast to YouTube, viewers often assume censorship or bias. In reality, the show is avoiding equal‑time obligations that would require them to offer identical airtime to every opposing candidate. The public interprets this as selective visibility, when it is actually compliance with a rule that only applies to broadcast television. The misunderstanding creates a perception of manipulation where none exists.

The Equal‑Time Rule also misleads because it creates the illusion of fairness while ignoring the platforms where most political influence now occurs. It regulates the least impactful medium while leaving the most influential ones untouched. It governs television but not streaming, broadcast but not digital, scheduled programming but not algorithmic distribution. As a result, the rule gives audiences a false sense that political communication is being balanced and monitored, when in reality the most powerful channels of influence operate entirely outside its reach.

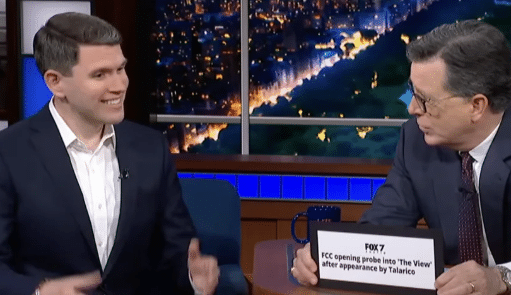

This confusion becomes even more pronounced when high‑profile entertainment shows attempt to navigate the rule. Programs like The Tonight Show, Jimmy Kimmel Live, and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert have all faced situations where inviting a political candidate onto the broadcast version of the show would trigger equal‑time obligations. To avoid this, they often release the interview online instead. The public sees this as a demotion or a deliberate attempt to hide the conversation. But from a regulatory standpoint, it is simply the cleanest way to avoid triggering a rule that applies only to broadcast television. The irony is that the online version often reaches more viewers than the broadcast version ever would.

Daytime talk shows face similar challenges. The View, for example, has had to navigate the Equal‑Time Rule for years. When a political candidate appears on the show, the producers must determine whether the segment qualifies as a bona fide news event, which would exempt it from equal‑time requirements. If it does not, the show risks having to offer equal airtime to every opposing candidate. This is not always feasible, especially during crowded primary seasons. As a result, some interviews are shortened, moved, or released online instead of airing on television. Viewers often interpret these decisions as political bias, when in reality they are logistical responses to a rule that no longer fits the modern media environment.

Even news programs, which are often exempt from the rule, face public misunderstanding. Morning shows like Today and Good Morning America regularly interview political candidates as part of their news coverage. These interviews are exempt from equal‑time requirements because they fall under the category of bona fide news events. But many viewers do not understand this exemption. When one candidate appears on a morning show and another does not, audiences assume the network is violating the Equal‑Time Rule. In reality, the rule does not apply. The misunderstanding fuels accusations of bias that have nothing to do with the actual regulations.

The Equal‑Time Rule becomes even more misleading when applied to comedy shows. Saturday Night Live has famously triggered equal‑time obligations by featuring political candidates in sketches. When a candidate appears on the show, even in a comedic role, the network may be required to offer equal airtime to their opponents. This has led to absurd situations where candidates who have no interest in appearing on SNL are offered airtime simply because their opponent participated in a sketch. The public sees this as favoritism or political messaging, when in fact it is the network following a rule that was never intended to govern comedy.

The rule also misleads by creating the impression that television remains the dominant force in political communication. It does not. The most influential political content today is not broadcast on television. It is streamed, clipped, shared, reposted, and algorithmically amplified across platforms that the Equal‑Time Rule does not touch. A candidate’s appearance on a podcast can reach millions. A viral TikTok can shape public opinion more than a televised interview. A YouTube conversation can generate more engagement than a primetime news segment. The Equal‑Time Rule regulates the medium with the least influence while ignoring the mediums with the most.

This mismatch between regulation and reality creates a distorted public understanding of how political communication works. People believe the Equal‑Time Rule ensures fairness across all media, when in fact it applies only to a shrinking portion of the media landscape. They believe networks are violating the rule when they are not. They believe online distribution is censorship when it is compliance. They believe platform decisions are political when they are procedural. The rule misleads not because it is being abused, but because it is being misunderstood.

The deeper issue is that the Equal‑Time Rule has not been updated to reflect the realities of digital communication. It was created for a world where television was the gatekeeper. Today, there are no gatekeepers. There are only platforms, algorithms, and audiences. The rule cannot regulate this environment. It cannot ensure fairness in a world where influence is measured in clicks, shares, and watch time rather than minutes on screen. It cannot address the power of digital platforms that operate outside the reach of broadcast regulation. It cannot keep pace with a media ecosystem that evolves faster than legislation.

The Equal‑Time Rule is misleading because it gives the public a false sense of fairness in a media environment that is anything but fair. It suggests that political communication is being balanced when it is not. It suggests that networks are obligated to provide equal visibility when they are not. It suggests that television remains the central arena of political influence when it does not. The rule creates expectations it cannot meet and perceptions it cannot correct.

The solution is not to abolish the rule, but to clarify it. The public needs to understand what the rule does and does not cover. They need to understand why certain interviews air on television and others appear online. They need to understand that online distribution is not censorship. They need to understand that the rule applies narrowly and inconsistently in a world where media distribution is broad and fluid. Without this clarity, the Equal‑Time Rule will continue to mislead the public and distort the conversation about fairness in political communication.

The Equal‑Time Rule was created for a world that no longer exists. It is time to stop pretending it governs the world we live in now. We want to hear your voice!