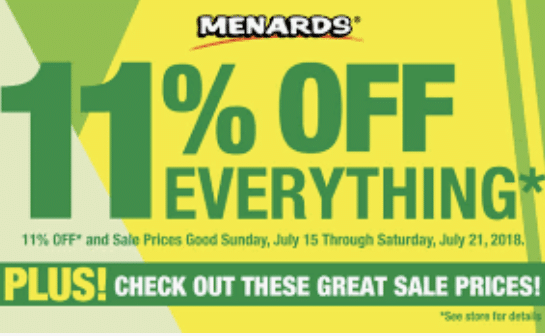

12/22/25 4pm MST: David Ravo, Misleading.com Sr Editor. Months ago, while wandering a Menards in Idaho, I spotted a bold “11% reduction” sign hanging over the aisles. I’ve liked Menards ever since I first saw their logo streak across a NASCAR hood, but misleading advertising is a very different kind of race. When a company crosses that line—especially one now facing a $4.2 million penalty—it stops being folksy Midwest charm and becomes something else entirely.

Menards’ 11% Mirage and the $4.2 Million Lesson in Misleading America

I was in a Menards in Idaho months ago when I first noticed the familiar “11% Off Everything!” sign hanging above the aisles. It was bright, bold, and unmistakably confident — the kind of sign that doesn’t ask for your attention so much as it demands it. I’ve been a fan of Menards ever since I saw their logo streak across the side of a NASCAR years ago, a symbol of Midwest grit and weekend‑warrior optimism. But there’s a difference between nostalgia and reality, and when a company’s advertising misleads its customers, that’s a whole other story altogether. The Menards I admired for its practicality and straightforwardness had quietly become a case study in how a beloved brand can lose its way.

The 11% promotion wasn’t just a sale. It was a cultural event. Contractors planned projects around it. Homeowners waited for it. People bragged about timing their purchases to it, as if they had cracked some secret code to beating the system. But the truth behind the promotion — the truth that eventually triggered a multistate investigation and a $4.2 million penalty — was far less charming. Menards wasn’t offering an 11% discount at all. It was offering a rebate, and not the kind of rebate most people imagine. This was a delayed, conditional, store‑credit‑only rebate, wrapped in fine print and marketed in a way that regulators later described as deceptive.

The heart of the issue wasn’t the existence of a rebate. Rebates are legal. Rebates are common. Rebates are a marketing tool as old as American retail itself. The problem was how Menards presented it. The company’s signage, advertising, and in‑store messaging created the unmistakable impression that customers were receiving an immediate discount at the register. The words “11% Off Everything!” were not accompanied by equally prominent disclosures explaining that the savings would come later, in the form of store credit, after customers filled out paperwork, mailed it in, waited weeks, and then returned to Menards to spend the credit before it expired.

This wasn’t an accident. It was a strategy, State investigators found that Menards often displayed prices that already reflected the 11% rebate, making customers believe they were paying a reduced price when they were not. The company also implied that “Rebates International,” the entity processing the rebates, was a separate company — when in fact it was part of Menards itself. And during the pandemic, Menards was caught engaging in price gouging on essential items like purified water and isopropyl alcohol, a move that further eroded trust and added fuel to the investigation.

The result was a multistate enforcement action that ended with Menards agreeing to pay $4.2 million in penalties and to overhaul its advertising practices. The settlement requires the company to clearly disclose that the rebate is not an instant discount, to stop implying that customers will save money at the register, to be transparent about the nature of Rebates International, and to make the rebate process more accessible and less confusing. Menards did not admit wrongdoing — corporations never do — but the corrective actions speak loudly enough.

What makes this case so striking is not just the deception itself, but the scale of it. Menards is not a fringe retailer. It is a Midwest institution, a place where people buy lumber, paint, appliances, and Christmas decorations in the same trip. It is a brand built on trust, familiarity, and the idea that you can “Save Big Money at Menards.” But when the savings depend on customers not reading the fine print, the slogan becomes a punchline.

The psychology behind the 11% rebate is simple. When you break savings into two steps — purchase now, redeem later — fewer people complete the second step. This phenomenon, known as “slippage,” is well‑documented in marketing research. Companies count on it. They design rebate programs with friction points: forms to fill out, deadlines to meet, mail‑in requirements, long processing times, and store‑credit limitations. Every friction point increases the likelihood that the customer will never redeem the rebate. And every unredeemed rebate is pure profit.

Menards’ 11% promotion was a masterclass in slippage. Customers had to fill out a form, mail it in, wait weeks, track the rebate, and then return to Menards to spend it. If they lost the rebate, forgot about it, or missed the deadline, the savings vanished. But the marketing never emphasized these hurdles. It emphasized the number: 11%. Big, bold, and everywhere.

The problem is that customers eventually catch on. They start to notice that the discount they thought they were getting isn’t a discount at all. They start to feel misled. And once customers feel misled, the damage is done. Trust is not a renewable resource. It doesn’t regenerate with the next sale or the next promotion. It erodes slowly, then suddenly.

The $4.2 million penalty is significant, but for a company of Menards’ size, it’s manageable. The real cost is reputational. When customers lose trust, they don’t just complain. They change behavior. They shop elsewhere. They tell friends. They post online. They become skeptics instead of loyalists. And skepticism is contagious.

Menards’ situation is a reminder that misleading promotions are a short‑term strategy with long‑term consequences. They create temporary spikes in sales, but they also create lasting resentment. They undermine the very relationship that retail depends on: the belief that the price you see is the price you pay, and that the company you’re buying from is being straight with you.

What makes this even more frustrating is that Menards didn’t need to do this. The company already had loyalty. It already had brand equity. It already had a reputation for being cheaper than Home Depot and friendlier than Lowe’s. The 11% rebate became a crutch — a marketing gimmick that grew so big it overshadowed the truth behind it. And once customers realized the discount wasn’t a discount, the trust cracked.

If Menards wants to rebuild that trust, it needs to do more than comply with the settlement. It needs to embrace radical transparency. It needs to stop relying on rebate psychology to drive sales. It needs to offer real discounts, not delayed store credit. It needs to communicate honestly, clearly, and without fine‑print gamesmanship. The Midwest is forgiving, but it is not forgetful.

Menards is not the first company to learn this lesson, and it won’t be the last. The retail landscape is filled with cautionary tales — companies that pushed the boundaries of truth and paid for it in lawsuits, fines, and customer loyalty.

Red Bull settled a $13 million lawsuit after customers challenged its claim that the drink “gives you wings,” arguing that the slogan implied performance benefits not supported by science. Volkswagen suffered one of the most devastating brand collapses in modern history after it was caught installing software to cheat emissions tests. Kellogg’s had to walk back claims that Frosted Mini‑Wheats improved children’s attentiveness by nearly 20%. Skechers paid millions after marketing Shape‑Ups as a weight‑loss solution without credible evidence. L’Oréal was forced to abandon claims that its skincare products could “boost genes” or “stimulate youth proteins,” promises that sounded scientific but weren’t.

These companies all had something in common: they underestimated their customers. They assumed people wouldn’t notice, wouldn’t question, or wouldn’t care. They assumed that marketing could outrun reality. But reality always catches up.

Menards is now part of that list — not because it made a mistake, but because it built a marketing strategy around the hope that customers wouldn’t look too closely. The $4.2 million penalty is a headline. The loss of trust is the real story. And for a company built on the optimism of the American homeowner, that’s a cost no rebate can cover. We want to hear from you, what misleading promotions have you seen?