In 1981, novelist Walker Percy wrote a compelling editorial—in the New York Times of all places—about the near-term likelihood of a proposed constitutional human life amendment being enacted. After parsing the uncontested scientific evidence that abortion destroys a human life, he ended with this admonition to advocates of legal abortion: “According to the opinion polls, it looks as if you may get your way. But you’re not going to have it both ways. You’re going to be told what you’re doing.”

Apparently, they need to be told again. Frankly, the whole country needs to be told again. Because at the moment, the abortion debate looks like nothing more than a series of political firefights, unrelated to what we’re really “doing.” The questions driving today’s abortion discourse are all the wrong ones: Will Democrats, if elected, ditch the filibuster to impose unlimited legal abortion on the 50 states? Are doctors afraid to safely manage miscarriages or abortion pill-induced sepsis because of their (often mistaken) understanding of their states’ abortion limits? Will another red state constitutionalize abortion on demand, forbidding even popular guardrails such as parental involvement or informed consent?

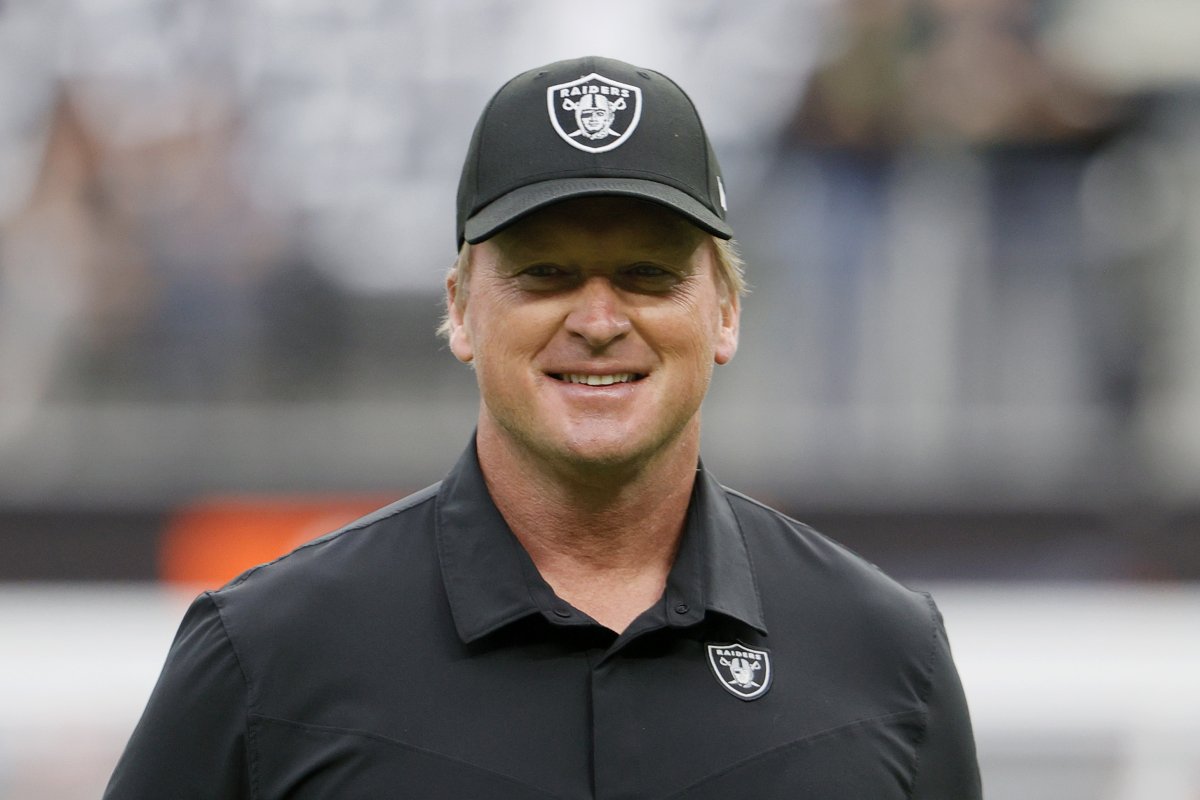

WASHINGTON, DC – JUNE 24: Abortion rights advocates participate in a protest outside of the U.S. Supreme Court Building on June 24, 2024 in Washington, DC. Abortion rights and anti-abortion rights activists demonstrated outside the U.S. Supreme Court to mark two years since the court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling, which reversed federal protections for access to abortions.

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

These questions are nearly completely distracting us from what we’re really “doing” when we legalize abortion: taking a side on a host of deep cultural, philosophical, even civilizational questions. Is America afraid of its future, its children? Does it begrudge them its time and money? Is motherhood so overwhelming and overwhelmingly negative that a presidential campaign could correctly believe that it can sweep to victory—counting especially upon female voters—by putting abortion rights front and center? Has America lost the plot of its civil rights and human rights stories? Previously, these brought special solicitude and protections for the more powerless human beings in our society. But today’s abortion rights campaign proposes that another’s powerlessness is precisely what justifies his or her being killed. And not by just anybody, but precisely by one’s own mother. Only the mother—the person nature first charges with the protection of the next generation—can consent to an abortion. Only family can legally kill family, and only when the target is utterly powerless. All in the name of human and civil rights.

If this is what the United States is moving toward, then this is the conversation we should be having this presidential election season. It’s infinitely more honest and more important than what we’re doing now.

And alongside this conversation, we need one about how to engage people’s fears—especially young adults’—about the future, and about marriage and parenting in particular. Have we really lost the sense that it’s better to have a fully committed partner for life, with whom to raise children? If that’s not attractive, why not? What is proposed as a superior way? On what evidence? Or, if abortions aren’t driven by a rejection of marriage and parenting—but rather by nonmarital sex divorced from “tomorrow,” by financial or employment fears, or by frightened boyfriends—then what concrete improvements in these spheres can we set to work on?

Pro-life candidates and interest groups should lose no time injecting these larger questions into what passes for our abortion debate this election season. They need to provoke reflection upon what legal abortion is and what it says about the United States. Otherwise, the public will never be told what abortion advocates are actually doing, hiding behind their big smiles, pink balloons, and thoughtless repetition of fake women’s rights slogans.

Helen M. Alvaré is the Robert A. Levy Chair and Professor of Law at the Antonin Scalia Law School of George Mason University, Arlington, VA.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.