David Ravo, Senior Editor, 12:00 PM 1/3/25

Sell By, Use By, Best Before: Three Labels, Zero Clarity, Billions in Wasted Food.

There’s a staggering amount of confusion baked into those little date labels—Sell By, Use By, Best By, and the rest of the alphabet soup stamped on our food. That confusion fuels billions of pounds of unnecessary waste every year. It’s time to cut through the fog and break down what these labels actually mean—and what they absolutely don’t.

Walk into any American kitchen and you’ll find a quiet, familiar ritual playing out: someone opens the fridge, spots a date stamped on a carton, hesitates, and then throws the food away. Not because it smells bad, looks off, or shows any sign of spoilage, but because of a tiny printed date that most people assume is a warning of imminent danger. In reality, that date is usually nothing more than a manufacturer’s best guess about peak flavor, not a federally regulated safety deadline. Research shows that most consumers misunderstand these labels, and that misunderstanding fuels billions of pounds of unnecessary food waste every year. The tragedy is that the labels were never meant to be interpreted this way. They were created to help, not to scare, and yet they’ve become one of the most effective accidental misinformation campaigns in modern consumer history.

To understand how this confusion took root, you have to go back to the mid‑20th century, when American grocery shopping was undergoing a transformation. Before the 1970s, most food was sold through counter service. Clerks handled inventory, rotated stock, and advised customers on freshness. Consumers didn’t need printed dates because they relied on the grocer’s expertise. But as supermarkets expanded and self‑service shopping became the norm, customers were suddenly responsible for choosing their own products. Manufacturers and retailers began adding internal codes—known as “closed dating”—to track production and distribution. These codes weren’t meant for consumers. They were essentially batch numbers and timestamps for internal use.

Then something unexpected happened: shoppers started noticing the codes and asking what they meant. Retailers, eager to reassure customers, began voluntarily adding “open dating,” which used calendar dates to communicate when a product would be at its best quality. These dates were never designed to indicate safety, and they were never standardized. Each manufacturer used its own system, its own criteria, and its own language. By the 1970s, consumer advocacy groups began pushing for transparency, arguing that shoppers deserved to know how fresh their food was. But instead of creating a unified national standard, the U.S. government stepped back. Except for infant formula, federal law still does not require expiration dates on food products. The result was a patchwork of voluntary labels—“Sell By,” “Best Before,” “Use By,” “Best If Used By”—each created with good intentions but no consistent meaning. That lack of standardization is the root of today’s confusion.

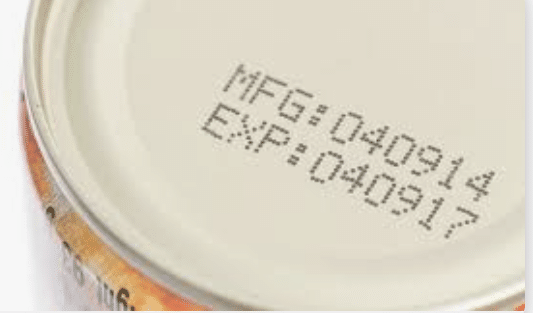

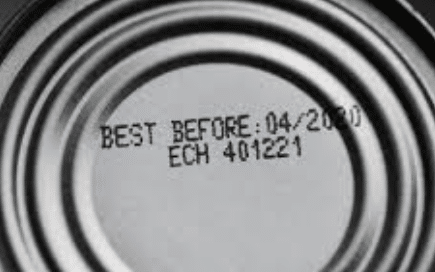

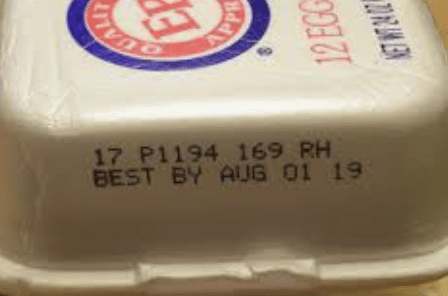

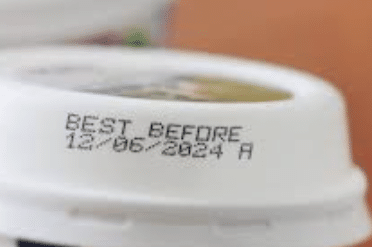

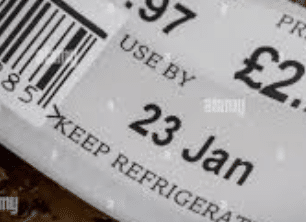

Despite the widespread belief that date labels indicate safety, the overwhelming majority refer only to quality. They are predictions, not warnings. Guidelines, not deadlines. And they vary widely depending on the manufacturer, the product, and the packaging. “Sell By” dates are intended for retailers, not consumers. They tell stores how long to display a product for inventory rotation and have nothing to do with safety. “Best By” or “Best Before” dates signal when the manufacturer believes the product will taste its best, but food is generally still safe after this date. “Use By” is the most misunderstood label. It refers to peak quality, not safety, except in the case of infant formula, the only product legally required to carry a true expiration date in the United States. “Freeze By” simply indicates when a product should be frozen to maintain quality. The common thread is that these dates overwhelmingly reflect quality, not safety, yet consumers routinely treat them as hard expiration deadlines.

If the labels were never meant to be safety warnings, how did they become interpreted that way? The answer lies in a perfect storm of psychology, marketing, and regulatory ambiguity. First, the language itself sounds official. “Use By” and “Best Before” sound like instructions. “Sell By” sounds like a deadline. None of these phrases intuitively communicate “This is just a suggestion about taste.” Without context, the average shopper assumes the most cautious interpretation. Second, Americans are conditioned to fear spoiled food. Foodborne illness is real, and people understandably err on the side of caution. But the dates on packaging rarely correlate with microbial risk. Spoilage depends far more on storage temperature, handling, and packaging than on a printed date. Yet the date is visible, simple, and easy to blame.

Manufacturers also benefit from shorter dates because they encourage faster turnover. If consumers throw away food earlier, they buy more. While not an intentional conspiracy, the incentives align in a way that reinforces conservative dating. Add to that the lack of federal standardization, which allows every manufacturer to use its own criteria, and you get a system that consumers cannot reasonably decode. Finally, cultural reinforcement plays a role. Generations have grown up hearing “Don’t eat that, it’s expired.” The phrase “expired” itself is misleading—most foods do not have true expiration dates. But the cultural shorthand stuck, and the misunderstanding became self‑perpetuating.

The consequences of this confusion are enormous. Between 30% and 40% of the U.S. food supply is wasted each year, and a significant portion of that waste comes from consumers discarding food prematurely because of misunderstood date labels. This waste has multiple costs. Financially, families throw away hundreds of dollars of edible food annually. Environmentally, food waste contributes to methane emissions, wasted water, and unnecessary agricultural impact. Socially, perfectly edible food is discarded while millions face food insecurity. The irony is painful: a system designed to reassure consumers has instead created a culture of over‑caution and waste.

Consumers deserve clarity, and until federal standardization arrives, the best defense is understanding what the labels actually mean and how to evaluate food safely. Trusting your senses is far more reliable than trusting a printed date. Sight, smell, and texture are better indicators of spoilage than any manufacturer’s guess. Storage matters more than dates as well. Milk kept at 40°F or below can last several days past its “Sell By” date. Eggs can remain safe for weeks after purchase. Proper refrigeration dramatically extends shelf life. It’s also important to know which foods truly expire. Infant formula is the only product legally required to have a safety‑based expiration date. For everything else, the date is about quality. “Best By” should be treated as a flavor guide, not a safety deadline. Canned goods, dry pasta, crackers, and spices often remain safe long after their printed dates. And “Sell By” dates should not be feared at all—they are for store inventory management, not consumer protection. Freezing is another powerful tool. If you’re unsure you’ll use something in time, freezing pauses spoilage and preserves safety.

The current system is a classic example of well‑intentioned transparency gone wrong. Consumers want clarity. Manufacturers want flexibility. Regulators want safety. But without a unified standard, the system fails everyone. Several proposals have emerged over the years, including a two‑label system—one for quality (“Best If Used By”) and one for safety (“Use By”)—as well as mandatory educational campaigns and federal standardization of terminology. Some manufacturers have voluntarily adopted clearer language, but adoption is inconsistent. Until reform becomes widespread, consumers remain stuck navigating a confusing landscape.

Food date labels are not the villains they appear to be. They were created to help, not mislead. But decades of inconsistent terminology, lack of regulation, and cultural misunderstanding have turned them into one of the most confusing elements of modern grocery shopping. The truth is simple: “Sell By” is for stores, “Best By” is about taste, “Use By” is about peak quality rather than safety (except for infant formula), and most food is safe beyond the printed date if stored properly. Consumers deserve better than a system that quietly encourages waste through ambiguity. Until the United States adopts a standardized, transparent approach, the best tool we have is knowledge—understanding what these labels mean, what they don’t, and how to make informed decisions without being misled by the fine print. Clarity shouldn’t be optional, and food shouldn’t be wasted because of a misunderstanding.

In the end, it’s all about understanding what an expiration date truly represents. Manufacturers set these dates using conservative estimates based on taste tests, shelf‑life modeling, and quality benchmarks—not on safety thresholds—and they intentionally err on the side of caution to protect brand reputation. That means the “expiration date” printed on most foods is far more about preserving peak flavor than preventing illness. In most cases, the food doesn’t suddenly become unsafe or “go bad” the moment that date passes; it simply may not be at its absolute best. When consumers recognize that these dates are quality guidelines rather than hard safety deadlines, they can make more informed choices, waste less food, and navigate their kitchens with confidence instead of fear. We want to hear from YOU !